Memo to McFadden: DWP

What does Labour's new "super ministry" mean for welfare reform, skills policy and the future of work? Tom Bewick provides some unofficial advice to the minister.

Dear Secretary of State,

With just over a year into government, the prime minister has handed you one of the most critical briefs in cabinet.

It’s understandable. Economic growth has not materialised at anything like the rate required to reduce debt interest on UK borrowing, or to sufficiently boost the pay packets of every working family in the country.

Labour backbenchers scuppered your predecessor’s attempts to reduce the ballooning welfare bill—with one-fifth, that’s 9 million people of working age, who are economically inactive. Nearly a million young people are NEET (not in education, employment or training).

In amongst the gloom, however, there are some encouraging signs. The statutory national living wage increased by above-inflation rates, 6.7% for those 21 and over (18% for apprentices). It comes on top of private sector wage settlements (adjusted for inflation) of 1.5% excluding bonuses. While unemployment has increased by 260,000 since Labour came to power in July 2024, Labour Force Survey data suggest that employment levels have also risen.

Additional capital investments in house building, defence procurement and renewable energy should soon start to show up in the real economy. The challenge for the Bank of England will be to ensure the situation doesn’t spiral into stagflation, characterised by rising unemployment and inflation.

It’s a mixed picture in the labour market and one your officials and advisers will need to monitor closely as the new Employment Rights Bill becomes law, and possible further tax rises in the autumn Budget kick in. Both of these developments have the potential to reduce payroll employment still further.

Think of your new role as the “growth enforcer” across Whitehall. While you consolidate your super Department’s remit, may I offer some humble advice on areas you might want to pay some particular attention to?

My advice covers the Union, Personnel, Policy and Programme Reform.

Use your UK-wide remit to coordinate the British labour market better

One of the most underutilised tools of your Department is the fact that employment policy is reserved for Westminster. While devolution in the four nations since 1998 is a process, not an event, it is undoubtedly in the interest of every UK citizen that the common labour market across these islands and different jurisdictions operates smoothly.

Indeed, under the last Labour Government (1997-2010), programmes such as the New Deal, Sector Skills Councils, and the UK Commission for Employment and Skills all operated on a four-nations basis. This helped coordinate the labour market in areas such as establishing common standards for apprenticeships and ensuring that all citizens could access employment support and adult training opportunities regardless of their postcode (or the political administration in which they live).

This common approach to employment and skills has been allowed to unravel since 2010. While devolved ministers can expect to make decisions on education policy (which is delegated to them under the terms of primary legislation), it does not follow that they should automatically make decisions about employment and skills policy, which cuts across the interests of British firms that hire people and apprentices in Scotland, England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

There is already Westminster legislation on the statute book, such as the UK Internal Market Act 2020, and the Professional Qualifications Act, which empowers you to coordinate skills, qualifications and apprenticeship policy on a UK-wide basis should you choose to do so. Moreover, applicable provisions of the Employment and Training Act 1973, which are still in force, give you the power to establish UK-wide labour market bodies.

It could prove particularly useful by simply reshaping Skills England into Skills UK.

When examining the current remit of Skills England, which includes gathering labour market intelligence and advising ministers on “simplifying the landscape” to boost jobs and growth, it is clear that this should be done on a four-nations, UK-wide basis.

I advise you to seek Treasury approval for FY 2026-27 for the proposed UK Growth and Skills Levy, to be routed entirely via your Department, rather than being apportioned to the Devolved Administrations (DAs) as part of the current Block Grant and Barnett Consequential Arrangements.

The OBR forecasts that the Levy will raise about £4 billion in this financial year on a UK-wide basis. These are funds that, in the future, could be routed via your UK-wide department.

The benefits to employers and training providers, working with the established network of local JobCentres that already operate across the UK, would be immense. For example, it would mean that employers working across the DAs could access apprenticeship support via a single HMRC Digital Account (currently, this facility is only available to employers in England). Moreover, by adding representatives, including industry leaders, to the new Skills UK Board, it should be possible to develop national occupational skills standards for the whole UK in the future (as was the case before 2017).

All these measures not only have the potential to streamline funding. They will also encourage economic growth and the uptake of more apprenticeship opportunities, as red tape and regulatory barriers across the UK will be significantly reduced. Some of your officials and vested interests will tell you this is all impossible, but in fact, it is the right thing to do in the interests of the UK’s common labour market and the freedom of movement of apprentices.

The change will also ensure that all companies can benefit from the provisions of the proposed UK Growth and Skills Levy, which promises more flexibility to upskill and reskill the British workforce. The danger otherwise is that the DAs will take the money as part of the block grant arrangement and not actually use it to upgrade the skills of the workforce. You can seize this opportunity to stop that from happening.

Get the right people in place

You have an experienced minister of state in Baroness Jacqui Smith, who will jointly report to you and the education secretary, Bridget Philipson.

My advice would be to establish clear rules of engagement between the two departments, ensuring they are fully transparent to both the Prime Minister and the general public. It makes sense that UK apprenticeship policy and the Adult Skills Fund (distributed currently via English Strategic Authorities) sit firmly in your brief. It will enable your officials to better align employment and welfare support with the delayed post-16 Education and Skills White Paper. The relationship with metro-mayors can also be reset.

It is clear from speaking to sources that the current draft of the White Paper is stuck. In particular, it lacks a coherent narrative of how skills demand can be boosted to tackle the country’s underlying economic weaknesses. Britain is trapped in a “low-pay, bad-job-trap” because of decades of underinvestment by both employers and the state.

Other challenges include how the operation of Universal Credit can be activated in ways that take more account of an individual’s current skills attainment and the potential, via targeted retraining, to direct them to areas where there are skills gaps and shortages. This will be essential if the government is to deliver on one of its other key priorities, which is to see net migration significantly fall by the end of this Parliament.

The current Skills Group in DfE is led by a Director-General who was in that position under the last Conservative Government. The individual concerned has no real experience in skills and labour market policy—her civil service background is in organised crime, COVID-19 response and school curriculum policy.

These changes to the machinery of government provide an opportunity to carefully examine the skills required of all senior officials to carry out the new Department’s remit successfully. It begins, therefore, by appointing yourself a new DG.

This is what the Skills White Paper should say

One of the first speeches the Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer gave, shortly after winning a landslide victory in July 2024, was about the country’s woeful lack of productive skills.

Focus policy on securing productive outcomes, not (more) processes

The biggest challenge you face is that the skills engine has become decoupled from the economic growth engine. How is it possible for the government to spend billions of pounds on adult skills initiatives each year and for these interventions to have zero impact on workforce productivity that boosts living standards?

Take the £300 million doled out each year by DfE on 16-week Skills Bootcamps. A government-commissioned evaluation found a success rate for individuals (defined as securing a job and maintaining it for 6 months following a course of training) of only 36.8%. It means that approximately £189 million was totally wasted, achieving no real-world labour market outcomes at all.

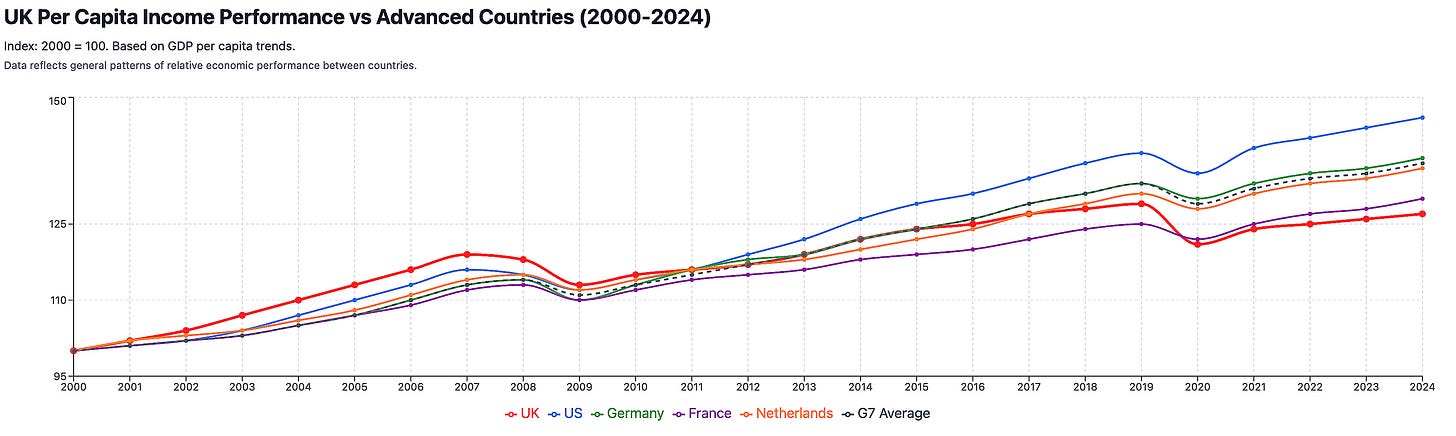

For much of the period of the last Labour Government, in the early 2000s, UK GDP per capita was growing at one of the fastest rates in the G7 (See Figure 1). Yet, since 2010, that position has been reversed—the UK is now languishing at the bottom of the league of rich countries. According to current trends, former communist countries like Poland and Slovenia are expected to be richer, on a per capita basis, than Britain by 2030.

Figure 1.

UK Productivity growth has averaged just 0.7% per annum since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis—the cause of today’s cost-of-living crisis. It explains so much of why workers are angry and voters are grumpy with their political leaders.

Suppose there is one overriding piece of advice I could give you. In that case, it is to ask every business lobby group, the training provider sector and the educational leaders who queue outside your door to see you, this key question:

What will your proposals do to increase the wages of ordinary British workers?

If they cannot simply answer this challenge, showing cause and effect in their answers, then it probably means that the skills policy ideas that they are putting in front of you are not worth the paper they are written on.

Say no to the special pleading for more money that routinely comes from the supply side. It’s time to end the era of performative schemes and reheated skills initiatives that civil servants design to give the impression that something meaningful is happening, when, in aggregate terms, Britain continues to slide into economic decline.

Shift your interventions onto the demand side

By publishing the delayed Skills White Paper, jointly signed by you and the Prime Minister, there is an opportunity to signal a significant shift in the government's growth mission agenda.

No longer about top-down tinkering with qualifications and supply-side reforms, such as mass immigration, but focusing instead on moving domestic talent and our businesses up the value chain. That requires a demand-side revolution in how we plan, coordinate and nurture world-class skills. The model of “Whitehall knows best” needs to be flipped on its head.

By targeting increases in per capita real incomes and placing emphasis on policy interventions by employers to create more good and rewarding jobs, it will be possible to reverse decades of failure in this area.

You can end the current postcode lottery in adult learning opportunities by passing primary legislation that gives every citizen a minimum entitlement to retraining, whether their employer or the state provides it.

Finally, if you are genuinely interested in understanding why Whitehall has failed to reverse Britain’s relative economic decline, I encourage you to read my new book.

Good luck!